At the beginning of May, I went to my first LARP, Run 3 of Wing and a Prayer. I had a fantastic time having a horrible time, and I wanted to write something about what I took from the experience, and the impression it left on me.

How It Works

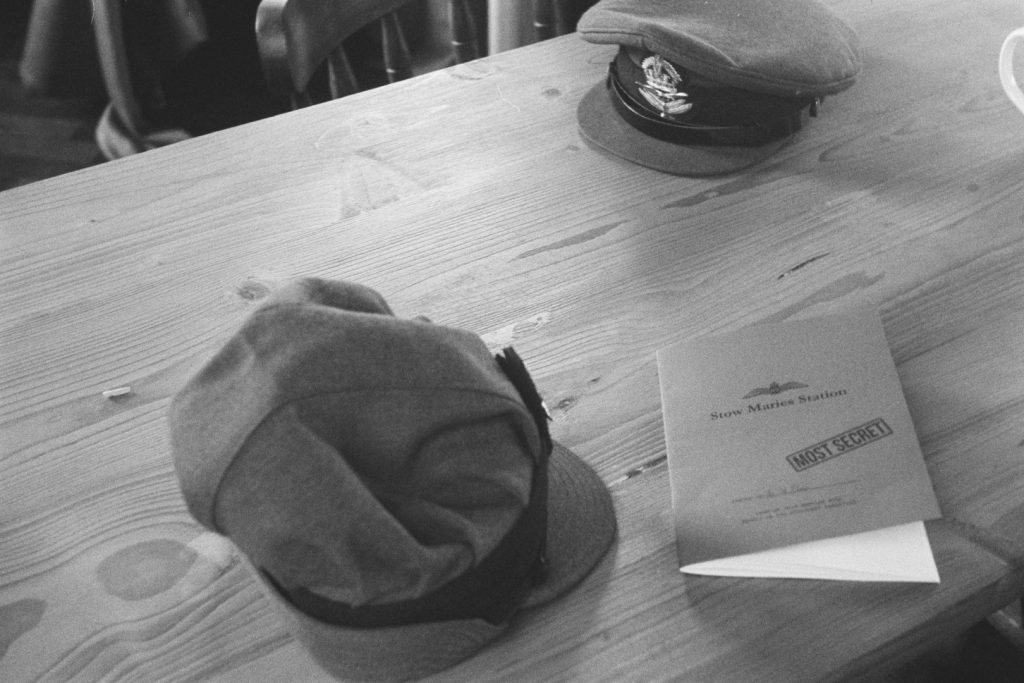

The conceit of the LARP is this: it is September 1940. In the skies above Britain, the Luftwaffe are attempting to destroy the Royal Air Force in order to allow an invasion. The aircraft of RAF Fighter Command are guided to intercept Luftwaffe raids from the ground, by a set of control rooms and a sort of distributed human computer for organising them known as the Dowding System. One of these control rooms is at RAF Stow Maries1, an airfield in rural Essex. Within the LARP, players playing male characters2 are Fighter Command aircrew. Players playing female characters are members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, the WAAF, and operate the Dowding System.

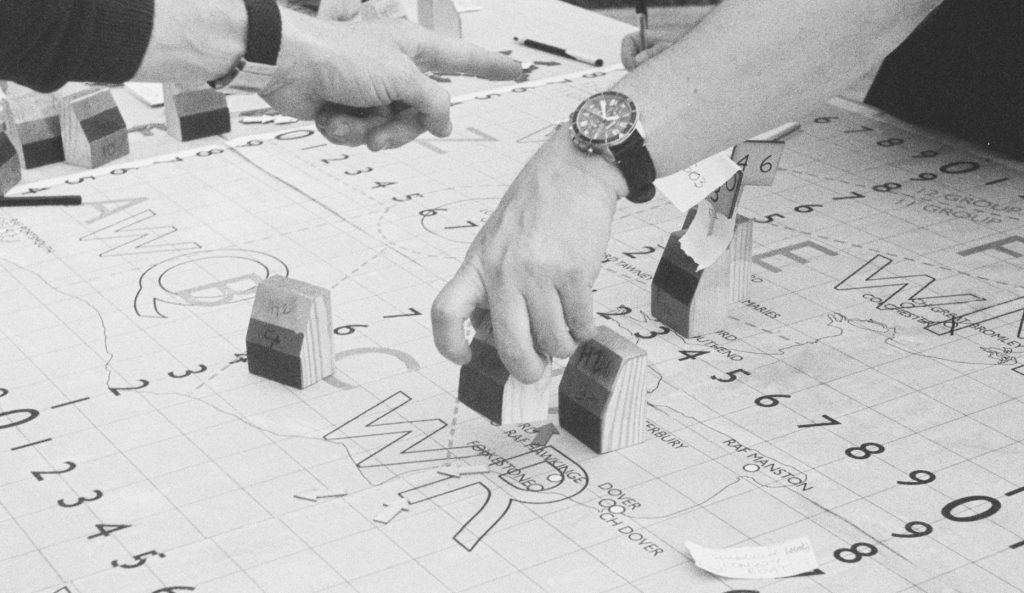

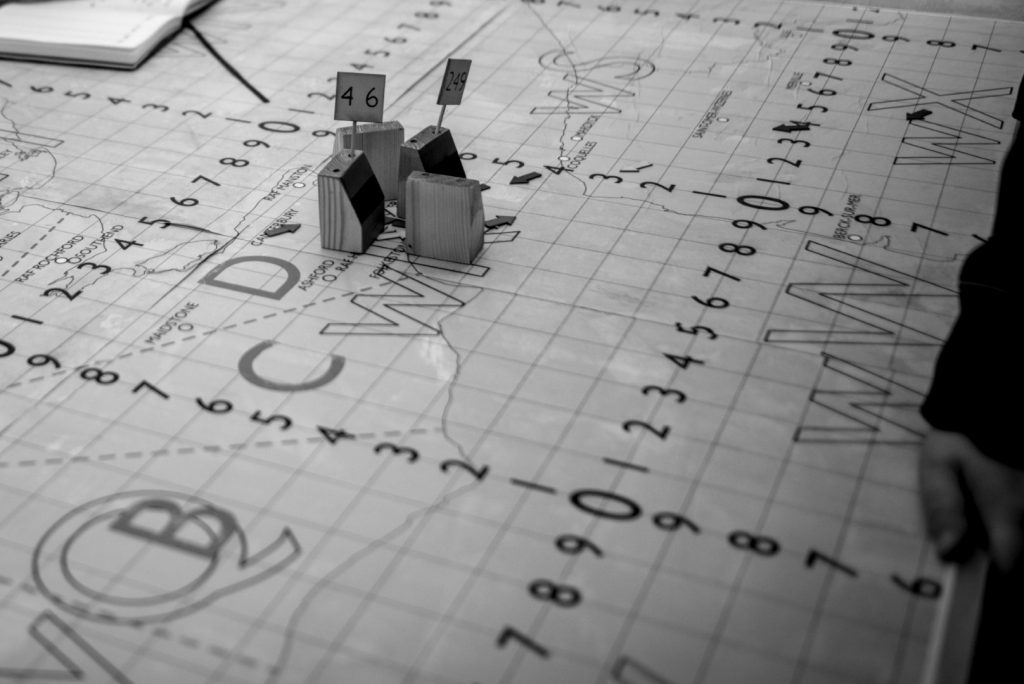

Although ostensibly a supporting role, the LARP itself is focused on these women and their experiences. Mechanically, this means both RAF and WAAF characters get time off duty to interact, but are often called to work staffing the control room, or to scramble to their ‘aircraft’ (computers simulating the aerial side). All of this requires real use of maps and grid references in what amounts to a mix of task LARP and wargame, a combination that is apparently (and lamentably) rare.

To explain how the Dowding System works, it’s helpful to understand it as a controlled flow of information. Three Chain Home (early RADAR) stations on the southeast coast of Britain – Great Bromley, Stow Maries and Dover – detect Luftwaffe formations over France. Chain Home operators report and track those readings. That information flows to a filter table, where they are interpreted and plotted on a map.

Then that information flows to an operations table3, which collates and plots them as well as reports from the Royal Observer Corps and early airborne IFF systems, to create a map of what is in the air, where it is, and where it’s going. That map is visible to the decision makers, who then order and direct RAF movements. All of that information is getting gathered and filtered and plotted to be presented to at most a couple of people. One of those people was me.

In an act of profound hubris4, I asked to be an officer, and as reward/punishment, was assigned the role of operations officer5. At the risk of vanity, within the wargaming side of the LARP, this is a role that veers dangerously close to ‘protagonist’. The operations officer is second in command of the room, and, following the orders of the watch supervisor who commands it, plans and orders the actual intercepts. So the workflow is this: recognise an enemy raid as it’s plotted, work out where it’s going and when it’s going to get there, then decide on a course of action that makes sense in terms of which squadron(s) should intercept it where and when, then convey those orders clearly to the squadron liaison, who actually talks to the aircraft over the radio. Lots of variables, lots of mental maths, and you without access to so much as a pair of compasses or a ruler, let alone a calculator. It reminds me of a Plan Ex but there are lots of them sequentially with far less thinking time. Depending on the watch supervisor and the situation, you might have a lot of latitude or a lot of guidance, but you are always responsible. Every job in the Dowding System is important, and complex, and difficult, but that side of the table with the operations officer and watch supervisor is the one with the most scope for judgment calls. It’s therefore also notable that historically, for much of the war this was a man’s job, done by an RAF officer. I’m grateful for the revisionism. My character is Section Officer (equivalent to a Flying Officer – in American terms a Lieutenant) Evelyn St. Clair, an upper-class disappointment who has spent the 1930s as a photographer and dilettante across Europe, from which she has made it out by the skin of her teeth, left only with a decent amount of trauma and something to prove.

Having explained what the job is, let me try to explain how it feels, using a very common action: scrambling a squadron. I look at the board of squadrons and see which are available and where they are stationed.

I look at the map and mentally make my intercept point. I turn over my shoulder to my squadron liaison and shout, “GROVES6, SCRAMBLE THREE OH TWO.” She is meant to call the airfield in question, and then our own ready room7. However, the telephone line to the ready room is broken. If I can offer one single piece of advice to the organisers: please, please always ensure this telephone line is broken. Because this means I then have to turn to the gallery of the control room, which always contains a few bored pilots, make hard eye contact with one of them, and shout, “RUNNER, SCRAMBLE THREE OH TWO.” He sprints out of the room. I hear him shout, “THREE OH TWO, SCRAMBLE, THREE OH TWO.” I hear that shout repeated by other, more distant voices. Someone rings the ready room bell. I hear boots pounding across grass and concrete. For what I know tactically to be an achingly long gap, but experience subjectively as about two and a half seconds, nothing happens. Then there are aircraft engine sounds on Groves’ radio. She speaks to them, moves them on the board to AIRBORNE, and tells me that they are so, in expectation of me having a grid reference and altitude to send them to.

What are we to take from this, apart from that running around and shouting is fun at any age? There is a particular moment in Patrick O’Brian’s novel Master and Commander, in which Jack Aubrey, captain of an 18th century Royal Navy sloop, internally debates whether to spend some of his precious and very limited supply of gunpowder on ordering target practice for his gun crews. Aubrey reasons his way to that decision, but not without ‘a voice within his inner voice — a voice from a far deeper level, “think of the lovely smell.”‘ Scrambling squadrons felt similarly. There might be good tactical reasons to do it, there might even be bad ones, but it never failed to exhilarate. You could feel it ripple through the whole room, and having the authority to make it happen was heady stuff.

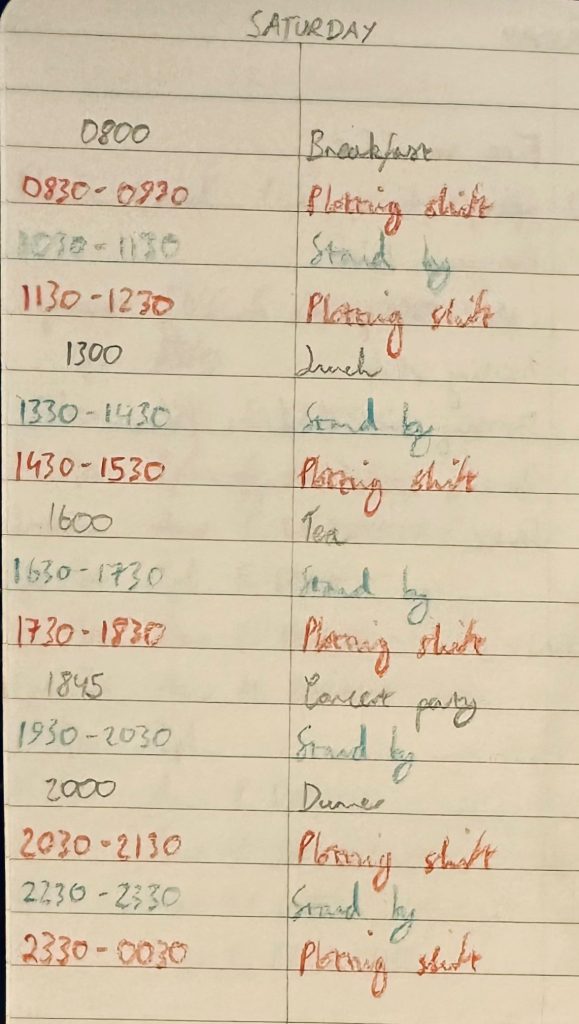

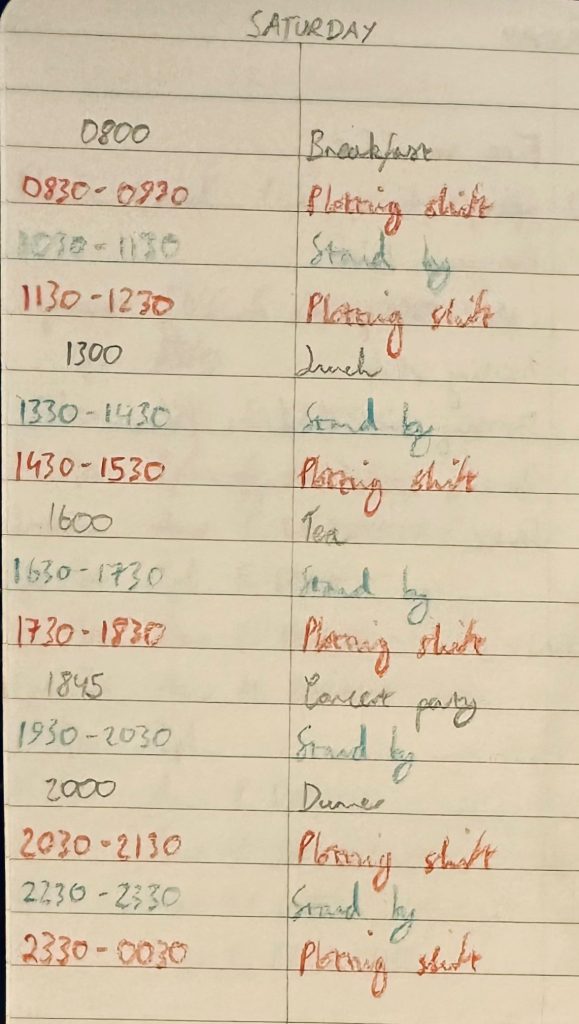

Wing and a Prayer is also a LARP about learning on the job, which is to say often learning the hard way. In the fiction, you are the emergency replacements after the proper sector control room has been bombed, which serves to cover over any lapses on your part, as well as any parts of the experience that might feel more improvised. As for the second part, I can confidently say I didn’t need any excuses. I was standing on duck boards in a temporary hangar half full of incongruous First World War biplanes, and none of it registered at the time, both because the team did such a good job of set dressing, because the other players did such a good job of roleplaying, and because from minute one I was thinking entirely in grid squares. The LARP is run over a weekend, so your training comes on the Friday, before a dance (dancing optional); you then get the whole of Saturday to play out, and Sunday morning is debrief out of character. This Friday training takes the form of a lovely man from the Post Office explaining it all to you. You should listen to him closely. It’s all useful information – Spitfires against fighters, Hurricanes against bombers, relative speeds, discerning a bomber raid from a deadly (and counterproductive to intercept) fighter sweep. He does, however, say some things which are not quite true – the Post Office being, as anyone who has seen that ITV drama, or heard a ‘sorry we missed you’ card drop onto their doormat as they fumbled with their dressing gown knows, a lying institution. Most saliently at this point, he says “we’ll generally only let you scramble three squadrons at a time.” Not so. You can leave the next watch like Chuichi Nagumo at Midway8, and while they will not thank you for it, there is nothing to stop you. Conversely, that handover between watches can be messy. There are three identical watches; Apple, Beer, and Charlie; these rotate between on duty, off duty and standby, to ideally give everyone a chance to get a mix of work and play. The watches are only an hour long9, but on standby you can and will be called in to assist at unpredictable times. You can see my schedule here:

All of this plus a system that can result in a confusing presentation of information, means that if the table10 gets irretrievably cluttered, you will be told that one good option is clearing it. Just get rid of everything. The ops table is meant to be receiving new information roughly every minute, so you spare yourself the task of untangling the entire Gordian knot and just see the latest as it comes in. Overall, the important thing is to maintain control of the table, to have a clear picture in your mind of what is happening where. Then, perhaps, you go off and dance a foxtrot or something and it all falls out of your brain.

Not so for me. I have a history of taking military-adjacent things too seriously that was honed in the finest environment for that task: being autistic in the Combined Cadet Force of a minor public school11. There used to be a running, and fruitless, competition to try and get me to smile on parade. If you put me in a situation with clear tasks and expectations, I don’t want to smile, I want to get a good grade, and helpfully I had worked out a character along those lines. Section Officer Evelyn St. Clair (more on her at the end) isn’t me, but she does have a worse case of a thing I have. Both she and I wanted desperately to make good intercepts, to be worthy of trust and confidence, to do the functional part well. Helpfully, I already like wargames, I can reliably pick out grid references (even using an antiquated phonetic alphabet), and I love dressing up and acting. So all of this comes quite naturally to me. The dancing less so, but that’s the trade-off of the character.

7th September, 1940

Come the morning and this pays off beautifully. For the first couple of shifts, Apple Watch and I make our intercepts perfectly. We disrupt our first raid without loss. When another comes with fighter escorts, we separate those with Spitfires and put a squadron of Hurricanes above and directly in front of the isolated bombers. Everyone seems to know their job immediately. We have excellent plotters, the squadron liaison is fast and reliable, I trust the Chain Home and filter tables completely, and most of all, we have our commander, Flight Officer Warren, a watch supervisor who both knows exactly what to do, and trusts me enough to delegate to me. At the end of the second shift, I tell the watch what a good job they’re doing, and that I’m proud of them. I still am.

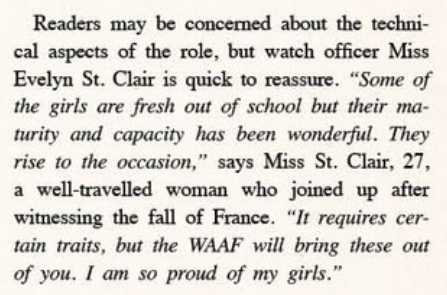

Off duty, I get to bond with Atwood, Beer’s ops officer. Charlie is missing theirs, so we’re splitting their shifts between us. This means that we’re working all the time, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. I’m enjoying it, it’s good stress. On Charlie’s watches, we’re talent scouting for replacements we can train, and I realise I am thinking like an officer. I fear that, as much as I’ve been able to evade it in real life, like the line from Conclave, God has made me a manager. Worse still, a middle manager. Coming off watch, I find myself ambushed in the mess by a reporter from Ladies’ Home Companion and instinctively give her an answer that could be on recruiting posters:

As morning ticks onward, my biggest challenge is having to contend with a very different culture on Charlie watch. For one, I am having to instruct as I work. For another, I am a sort of hired gun – I do not know these women, and after each shift they temporarily become Atwood’s problem again. The differences aren’t all bad; I have surprised myself by becoming fond of how upbeat Apple watch can be when things are going well. Clark, who manages the phones going to the Observer Corps and the Chain Home stations, is garrulous and funny, and I find myself being carried along. But Charlie’s plotters are all business; they stay focused and cold. But the reason they stay focused is their watch supervisor. If Flight Officer Warren is an easy commander to work for, Flight Officer MacLeod is not12. I come to think of her as a fighting captain. She is here to close with and destroy the enemy, and she takes that task completely seriously. All well and good, but she does not know me, does not appear to trust me, and takes a very hands-on approach that borders on the indiscriminate. As a result, I find myself acting mostly as an instrument of what I consider to be bad decisions. Charlie scrambles at the drop of a hat, routinely chasing after single enemy photo reconnaissance planes. These are high-reward but low-probability intercepts, wasting time and fuel charging squadrons up to high altitudes after one man and a camera who has long since gone home to get his film developed. We range far beyond the area we are defending. Chasing a Chain Home contact to Calais (I mentally wonder if, left to our own devices, Berlin would be next), we run a squadron into twice their number of enemy fighters. Our pilots make a hasty exit, taking the decision out of our hands. Throughout, I bite my tongue and do as I am ordered. Later, I will wonder if I had too much ego or too much timidity; if I had shown more charm or more aggression, would we have worked better together? But in the moment, it is a relief to finish one of Charlie’s watches and come home to Apple, who always follow them.

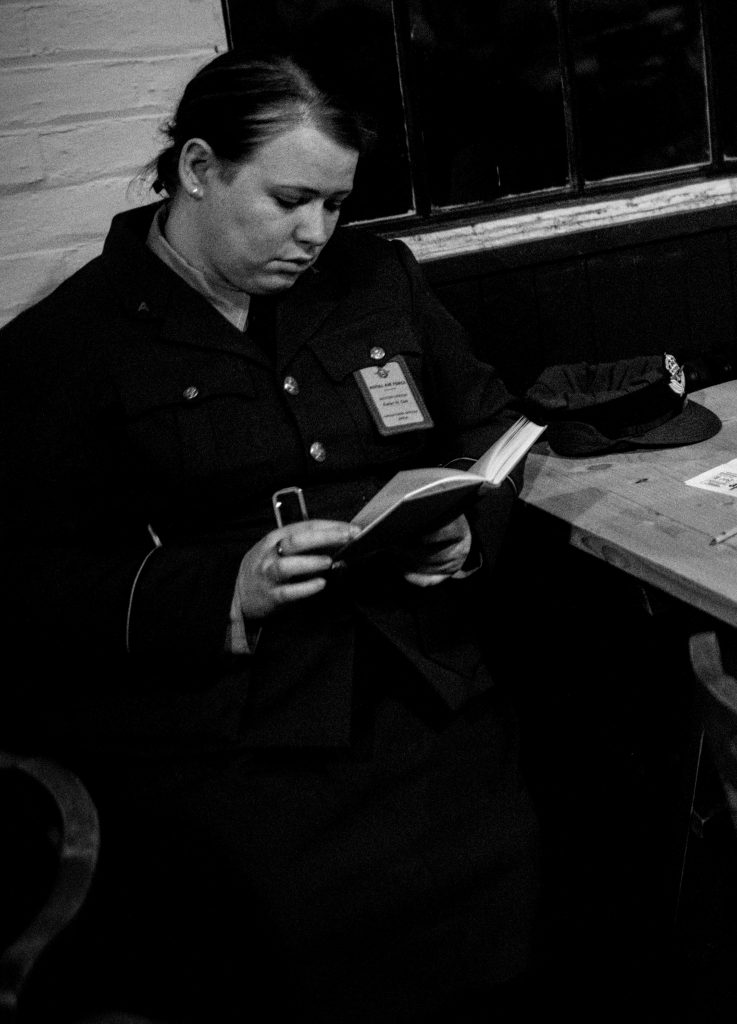

The only things keeping me up are MacLeod and those watch changeovers. For the moment, I write off both problems as insoluble, and spend my time reading my little book of Rilke poems in the mess and thinking about the shape of southeast England. It’s lonely, but command is supposed to be, and frankly I take a little pleasure in being aloof and technical. I talk shop with Atwood but make little conversation otherwise. At the end of the day it will occur to me that I have not once loosened my tie or opened my jacket.

WM5542

Throughout the morning, Chain Home across all three watches has been irritated by the slow progress of a British convoy around the south coast and into the Port of London. It is trailing barrage balloons, just high enough to return a reading. Often, this convoy makes it onto the ops table, an annoying distraction, another block in the way of everything. MacLeod has taken to marking its position with a slip of paper to better ignore it. I am aware that as I come on duty to cover Charlie’s third shift of the day that it should be cluttering up the Thames estuary for all of that shift and the Apple shift that follows it.

So it proves. The convoy is constantly reported as a new contact, and every time the operations table has to litigate whether or not it should be a new wooden block or the same slip of paper. As I am being ordered to chase down every other stray and transient contact, a curious thing happens. Something is forming over France, unusually far south, right at the bottom of our map. MacLeod and I both note it. It heads north for a moment, and then we lose track of it. An orphaned block sits over France, quite literally beneath our eyeline. I ask to put something in the way of it. MacLeod, distracted by channel traffic, ignores or does not hear me.

We catch one more glimpse of it, about to broach the coast of Normandy, still heading north. I ask permission to intercept it. MacLeod turns me down. I ask again, and she does not look at me. It is very nearly the end of Charlie’s shift. Perhaps she is worried about the handover too. Perhaps she is thinking of the hot tea in the mess. Perhaps she is thinking of other bombers in other places spiralling down through the clouds in flames. I cannot say. Judgment calls. I ask one more time – I urge. She refuses, and she is my court of highest and final appeal. I, who have found myself to be a middle manager13, do not shrug and do not sigh but look at my wristwatch and count the seconds until help arrives.

Warren arrives at the table, Charlie departs, and within seconds we are in business. We might be surgeons looking down at an ailing patient. I want to scramble, she concurs, and we do so immediately. Running and shouting. My pulse quickens. But I know – it has been weighing on me – that there is always a lag as one watch takes over from another. No matter how good we are, it takes time, and that is time we are without information. Our contact, our putative raid heading northwards, will have disappeared into the fog of maybe-naval-maybe-not probables and possibles now clogging up the Thames estuary completely.

Before we can get new data in, the convoy reports aircraft overhead. They cannot say how many, what heading, or in which direction. Inwardly, I curse the Royal Navy and the Merchant Navy in equal measure14. Suddenly our filter table and Chain Home are at work and new contacts land on top of our old contacts. And here is where I fool myself. All of these contacts are heading west, up the Thames. And I think, why not a change of direction? Why not up the Thames to bomb the docks ensuring the country does not starve? An easy, practical course to follow in full daylight. When the squadron we have sent up asks for orders, I send them east of London, to await enemy bombers heading west.

For the time it takes them to get there, and wait, and wait, nothing seems to happen. I do not know what is happening in the Thames estuary. I cannot see the new markers for the old markers. I can make no sense of the table15. With the picture hopelessly confused, I do as I have been taught and clear the board. And wait.

The next report puts an unescorted Luftwaffe bombing raid well north of the convoy, somewhere I wasn’t looking, three small grid squares away from the Chain Home station at Great Bromley. I know they will close that distance in around five minutes. I am scrambling the two nearest squadrons before this even fully registers. Clark is on the phone with one of the WAAF radar operators stationed there. I cannot hear her, but from Clark’s side of the conversation I surmise that she is young and she is scared. I know I have no time to intercept the raid, except perhaps to catch them on the way back over the sea. I have personally driven the squadron over London entirely out of useful range, to see nothing and do nothing. I scramble more squadrons. In the end I send up everything I have, with a mental apology to the next watch. And I miss all my intercepts. They are evacuating at Great Bromley. I can hear the pilots – all the pilots – get frustrated and sarcastic with Groves, my liaison. Clark can’t get her WAAF on the phone any more. We have no idea if she made it out. Finally, I get a squadron over the Chain Home station. It is a smoking ruin. I chase the raid out over the sea. All their would-be pursuers find is the convoy, which calls in a message thanking us for the escort. I land all my squadrons. Dead silence in the control room. I find I am staring at Great Bromley on the map. WM554216. I keep staring. The watch are trying to reassure me. I don’t hear any of it until Carrington, my youngest plotter, so young I wonder if she lied about her age to enlist, looks up at me and breaks my heart into pieces by saying, “We trust your judgment, ma’am.”

This is when I put my head in my hands. I look at my wristwatch. There is still half an hour of the shift left. Nothing is happening. A third of our ability to see raids approaching is gone. I stare hard at the table. It doesn’t take long for some of the returning pilots to barge into the control room. They are angry, but the sepulchral atmosphere takes some of it out of them at once. I try to volunteer myself, to explain that it’s my fault, but my voice dries up in my throat. Davenport, the best of my plotters, the one I would choose to take my job, is shouting at them. No-one could have done anything, she insists, it appeared out of nowhere. I pull her back, physically, and tell them that it is me they want to blame, and that they owe my liaison an apology. The whole succession of events has thrown them off balance, and they leave without much further protest. We close the doors behind them and finish the shift without event. I am still proud of my watch.

When the next watch comes on I have to explain to Atwood, which almost breaks me again. She is grimly resigned, and obviously furious. How could this happen? I don’t have an answer. I barely even understand the mistakes I have made. We get out of the room and I ask Warren, my watch supervisor, whether I should offer the Wing Commander my resignation at the end of the day or immediately. She is horrified, and tells me instead to take some time.

I head for the chapel, which is completely empty, save for stacked chairs and a silver crucifix on an improvised altar. I make absolutely certain that I am alone and that no-one is watching me, and then I start to cry. I stare at the crucifix and think,

“They’re not going to let me do this any more, are they?“

“How long does it take to repair a Chain Home station? To rebuild one? Months? Years?”

“I am Hitler’s secret weapon. What happened to Warsaw and Paris will happen to London and it will be my fault. They should put me in front of a firing squad.”

I try to think if there is anything in the Bible to help, and it occurs to me that scripture is curiously silent on the subject of incompetence. Every different kind of sin is addressed, but of simply trying your best and failing, I can think of nothing.

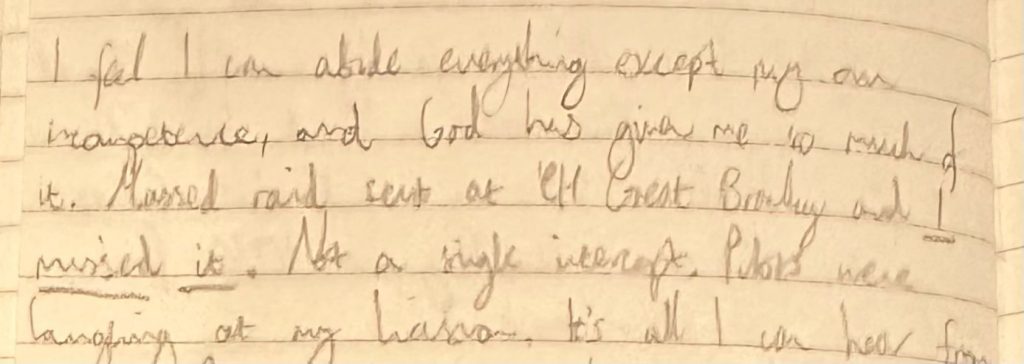

I write down in my notebook:

In the end it’s my filter officer who finds me. Langley. One rank my junior. Older. Similarly serious. I am fond of her. I ask if it’s a good idea for her to be seen speaking to the woman who just lost the war in an afternoon. She tells me that none of us have the power to do just as we wished, or the war would be won already. She tells me that I can still be good at what I do, that I still am. She gets me back on my feet and out of the chapel. Together, the officers of Apple watch try to work out how it happened. There are no satisfactory answers. Still, none of us realise. Something we all missed. The raid appeared out of nowhere, destroyed Great Bromley and vanished. What appears above is only what I can piece together, well after the fact17.

I spend a lot more time alone in the mess. It isn’t fun any more18. I am acutely aware that I cannot look any of the pilots in the eye. I read a line in the newspaper about the excellence of our air force and feel such a wave of disgust wash over me that I fairly throw it across the table. Back to my Rilke. Sonnets to Orpheus, I, 12. Hail to the spirit, that holds us together.

The Burning Blue

And we do pull it back together. There are other successes and other failures. I come on duty to discover that the Polish squadron at Tangmere have lost 9 of their 12 aircraft in a knife fight above their own airfield. Being Polish, the survivors beg and demand to be sent up again. I ignore them19. Other pilots trickle in to see the system working. This feels like someone else’s idea, to stop them seething at our, at my, incompetence. Perhaps if they see what we do, they will be more tolerant. I block it out. I am working, and there is much work to do. Whatever happens to me tomorrow – I am dimly aware of having seen Warren go off to speak to the Wing Commander in private – this cannot happen again today. See out the day. Keep control of the table.

Quietly, I put in a form for a transfer to photographic reconnaissance. I am astounded when Warren brings it back to me and asks me to tear it up. She tells me that the watch can’t spare me. I’m stammering out some kind of ridicule of that idea when she tells me that she is being promoted. And that she is recommending me to take her place as watch supervisor. She couldn’t guarantee anything, but would I be interested? I give the last sentence of Ulysses a run for its money. Somewhere in the back of my head I reflexively compare myself to the Wing Commander, who has been kicked upstairs to his current post after some rumoured debacle, and I wonder, but all I can discern is completely in earnest. I realise that if this is something I am going to do, I have to start looking the pilots in the eye again. Somehow I manage, and am surprised not to see total contempt there. I get word that poor Groves has been besieged all afternoon by successive pilots attempting to apologise to her. Mentally, I note that down on my list of bad intercepts.

The day heats up. There are no glasses so we are drinking water out of teacups. I live in terror of one of them spilling onto the map20. The pilots we send up into the burning sky are starting to come home injured, some horribly. More than once I find myself barking at Groves to turn off the speaker of her radio before the entire room hears a man’s death agonies. I am not always in time. My role and my work start to feel defensive. There is a documentary photographer there. He says he wants to create a ‘humanising narrative’. I tell him I can’t afford one. I cannot care, because if I care I will allow myself to be distracted again. Someone is playing ‘I Vow to Thee, My Country’ on the mess piano.

Incongruity reigns. There is a concert party/talent show in the mess. Two of my watch are adept comedians. Mid skit another squadron is scrambled and a handful of pilots have to fight their way out of the crowded room. Hardie, one of the pilots, alienates some more by singing ‘Solidarity Forever’. I find it in myself to join in. Evelyn is not a communist, but she has loved some, and it comes easily by way of honouring things they once held dear, even at the risk of her promotion. Conversely, I miss WAAFs vs RAFs cricket for two hours on duty. Just as well. I have been standing in parade shoes for so long that I don’t think I have any running left in me.

The worst death of the day doesn’t come with blood or any noise at all. Warren’s brother – I realise too late that I have never asked – simply disappears into the channel. When one of his brother officers comes to give her the news, she weeps onto the table. I mean to console her but all I can think to do is to put a hand on her shoulder. It takes all of us to get her outside and helped. I take over for the rest of the shift, and it means a lot that she trusts me to. She will rally quickly, quicker than I have. Pretty soon we are old hands at kicking bad news out of the control room. When a WAAF arrives to tell one of the filter plotters that her fiance is choking on his own blood on a stretcher, Langley roars at her to get out – too late to spare the girl, but enough to call in a replacement and keep the room running. I think that she is the backbone of the whole system.

The sun rolls down. The temporary hangar housing the control room changes instantly from burning to freezing. The last daylight shift feels like a drawing of curtains. Goodnight KOTEL21, goodnight GANER. One by one the day fighters get down and I think, we have made it through the day. One and a half shifts left of operating our comedy night fighters, the aircraft dignity forgot. They need special instructions, special attention and are crewed by pilots and gunners, our first enlisted men. They are fun and loose and make fun of each other on the radio. I surprise myself by kissing one of them in the doorway of the mess, an impulsive reward for his audacity in asking. I surprise myself again by tolerating a joke from Groves about it. Morning Evelyn would never have done this. It doesn’t matter how pretty you think some of the RAF are, it’s conduct unbecoming an officer. But we’ve all been through so much.

Things are drawing to a close. Later, a friend will draw a dream I have a few nights afterwards, which captures the feeling:

If you think there is any chance at all of you attending a future run of Wing and a Prayer22 – and you should – you should stop reading here and take this as a whole narrative. Skip down to the next heading, ‘Some Notes on Character,’ and pretend you didn’t see this warning or any of what follows.

Last chance.

Big Spoiler Warning

Wing and a Prayer is a trick. A simple trick, but one I fell for totally. You are exhausted and cold and your feet hurt because you have been standing in parade shoes on gravel for conservatively eleven hours at this point, and things really and truly feel like they are winding down. You have, legitimately, been through a lot. You’ve had an arc, even if in my case it was unexpectedly a rise and fall and then rise again. And here come those night fighters, about whom that nice man from the Post Office has been (justly) quite dismissive. They come up individually and more or less at random, you have to vector them into annoying patrol lines and stop them from shooting each other down, which is quite likely if they blunder into each other. You have an hour and a half to play with them before the whole game goes back in the box.

Or perhaps I should say I have an hour and a half to play with them. Let’s take another look at that watch rota:

If operations officer is a protagonist-coded job, then operations officer of Apple watch is doubly so, and something I’m immensely, uncomprehendingly grateful to have been handed. Because you’ll note that Apple watch is first in and last out. The final shift and closing everything down fell to me. I felt like a hotel night porter, or like a musician learning to play an entirely new genre of music, and I was gratified to discover that I was good at it, too. Different dance (and it does feel like one, notwithstanding the foxtrot on Friday). Different rhythm. It’s slower, and exercises different parts of the memory.

The trick is this: you forget, or do not know, the significance of the date 7th September 1940.

Earlier, in my shop talks with Atwood, before Great Bromley, I had said that we were alright protecting Chain Home stations23 and airfields24, but if the Luftwaffe ever changed targets, we would be in serious trouble25. And I distinctly remember saying, without guile or foreknowledge, “They’re fast learners. But nobody’s that fast.”

The whole day, you’re firefighting raids of maybe 40 bombers. Perhaps 100 if two or more raids merge. Even then, these can be effectively disrupted with two squadrons, something we pulled off beautifully a number of times. So in the early night, as it gets cold and you’re shivering inside your uniform and wishing for a greatcoat and a chair by the fire, to be told that 100+ bombers are forming up over France is to be woken up in a hurry. Then you have the realisation that you have to meet them with your slow and isolated night fighters. That drops the pit out of your stomach.

Roaring and trembling?

Alright. I follow my training and put them in the path of it, and then I am told there are another 100+ bombers. I call in the standby watch. Before they can get in the room, another 100+ appear. No no no no no not again this can’t be happening again. This is my fault because of Great Bromley and now there are another 100+ and my plotters are scrubbing out space on the unused blocks for more. Someone calls in the third shift as well. Suddenly I am barking complicated movement orders at Levine, Charlie’s liaison, because Groves is too busy to work the radios and talk. The three watch supervisors are all shouting over one another, giving me contradictory orders and arguing with each other.

True no hearing is whole

amidst all this raging

The room just keeps filling up. I am aware that the documentary photographer is there, and I snarl something at him about his humanising narrative. More counters are added to the table. I look at where it’s all pointing and this time it really is London. Part of me wonders at the possibility of making the same mistake twice, but it is left behind as the rest of me works at pace. I have Clark – no jokes, no banter now – call the Royal Observer Corps and order them to start sounding air raid sirens in London. I have never done this before. I don’t even know if I have the authority to do it, but it happens26. I get aircraft into combat but I can’t tell where because the radio and telephones are all jammed with useless reports of countless enemy aircraft and the East End of London is burning visibly from the air. I hear a choked sob as that gets read out and think coldly that someone must have family there.

See, how the machine heaves

And takes its revenge,

I have all the work I need, and the work is all I need. As I try to vector one useless night fighter around the northwest of London to stop it shooting down another one fighting in the southeast, I am dimly aware that I am crying. I do not stop working. None of us do. I understand this to be the bad ending, which we are experiencing collectively because I specifically have failed. The board is showing 1000 enemy bombers when we run out of counters to mark them with. The plotters are tearing up sheets of paper to make more. We are engaging those 1000 bombers singly. I have lost control of the table and now London is burning in front of our eyes. Strange, haunting music begins to echo out of Groves’ radio, amidst the gunfire and shouts. A woman is singing. I am aware of thinking quite clearly my first unambiguously non-Evelyn thought of the day: “I don’t know if that’s diegetic or not.” I do not stop working. None of us do.

Let it, without passion,

Urge us onward, and serve.

The LARP is called to a halt mid-action. It is announced that 7th September 1940 was the first night of the Blitz. We are asked to leave our stations and walk in silence to the mess. In the dark night outside I can hear others crying. I realise I don’t have to stop myself any more, that the rank braid on my sleeve is a costume, and I let myself weep.

We are seated in the mess where it is warm and light, and shown a video, which is a jolt because you are seeing a WMV on a projector screen after a day in the 1940s. My colleague and friend Abigail Thorn has a story about staying in character over a week in the woods doing Shakespeare, and experiencing a moment of total dissociation seeing a car for the first time at the end, and this felt similarly.

There’s a sentimental period song about the lights coming back on, and a montage of the casualties of the Blitz, area bombing of Germany and Japan, the pilots of Fighter Command, and the WAAFs who served and died with SOE in Europe. There is also, in passing, a note with two portraits of the Luftwaffe casualties of the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. Admittedly I was still in an emotional place, but I was not fond of this inclusion, not least because the Luftwaffe were engaged in a war of choice in service of a genocide, and in which they committed a number of directly attributable war crimes. I wasn’t expecting a big image of Arthur Harris with laser eyes and a chyron saying IT’S GOOD WHEN WE DO IT, but for me it left a sour note.

In any case, in the main I was left thinking of Ukraine and of Palestine. Over the weekend the LARP ran, during an ostensible ceasefire, Ukrainian air defence was attempting to intercept hundreds of Russian missiles and drones fired at them by a genocidal enemy waging a war of aggression against them. They were, and still are, doing the job we were pretending to do, with real consequences and another century’s worth of technological horror layered on top of it. Gaza, of course, does not have an air defence. If it did, it would be designated as part of a terrorist organisation. Over the same weekend, at least 23 Palestinian civilians were killed in a single Israeli air strike, part of a campaign of revenge for the attacks of October 7th that has had a nakedly genocidal character. Across the world, aerial bombing of cities is back in style, and we now live in a time more like that feared by proponents of the theory that ‘the bomber will always get through‘ than the resilience of the Blitz. That this is a result not of technological change so much as political change – a lack of will or even desire to enforce any kind of international law worthy of the name – is a bitter thing, and I was left feeling that we have squandered the sacrifices of that generation for peace. As I write this, No. 14 Sqn RAF is still providing aerial surveillance for Israel in Gaza. I have no illusions about the realpolitik of the British government, nor the colonial history of our armed forces, recent or ancient, but laid side by side it is an unedifying picture. I suppose that part of the point of the exercise is to try and remember and honour a time when the tides of history happened to make Britain an antifascist power, and for me part of that is an expression of hope that it can be so again in a consistent way.

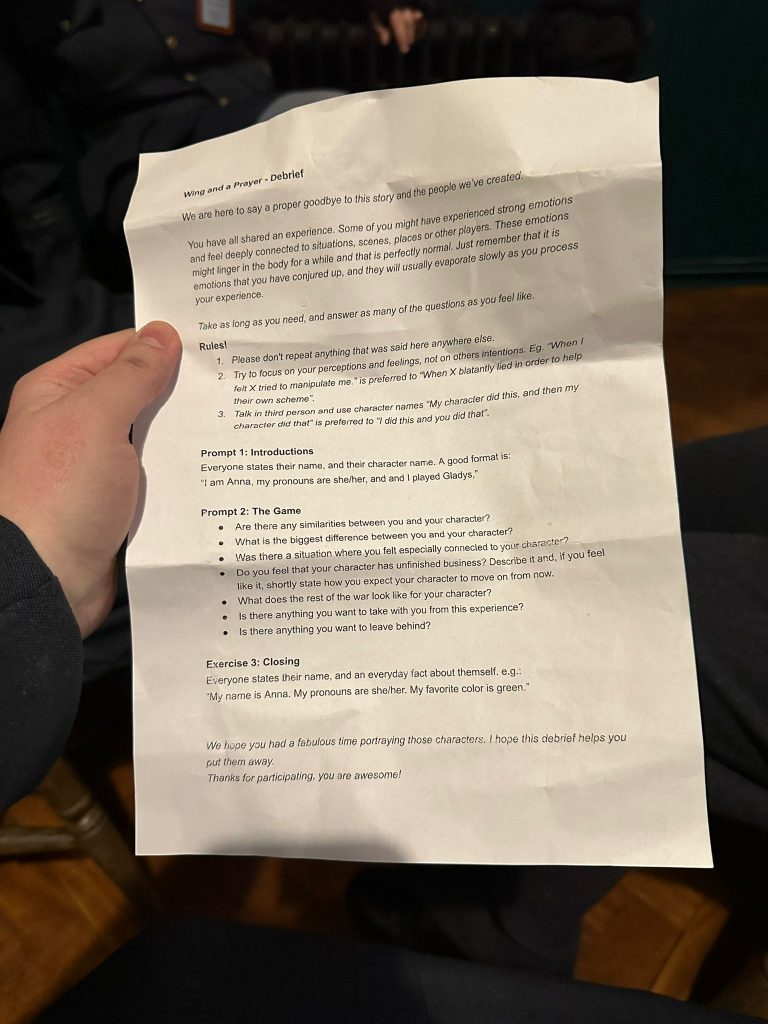

After the video, we did a little voluntary debriefing exercise:

And I got back to the hotel exhausted. I could have stayed in a tent on the airfield, but it really aided the officer-ness to have a billet with a shower and a bed. Not to mention the secret pleasure of having/getting to walk through a bit of Chelmsford in uniform in a way that wasn’t technically stealing valour. Just as a testament, here’s a selfie taken right before I put my phone away and got into character for the weekend, and one taken on getting back to the hotel after my last watch:

The next morning, before everything got packed up, we got the chance to see the other side of the LARP, as well as a debriefing. Obviously, being me, I wanted to know if I got a good grade, and surprisingly the answer was ‘sort of’. Apparently Great Bromley has been destroyed in all three runs (although not by necessity – it can be saved, and I got the sense that it is not usually destroyed this embarrassingly). On the other hand, no-one had ever made the first intercept we made before. We get some historical context, notes on accuracy (exacting, thanks to Torsten, the man running the simulation side, going through Luftwaffe ORBATs in detail), and the revelation that last night there were 442 bombers attacking London. We shot down two, which I’m told in the circumstances is not bad.

It’s a delight to get to see it all more casually – I’m amazed by the RAF side. I also get the chance to meet people out of character I didn’t get much opportunity to interact with in character. Everyone is lovely, and I am astounded when a couple of them tell me that they know who I am and enjoy the podcasts. We really do have people everywhere, it seems.

Some Notes on Character

Section Officer Evelyn St. Clair still interests me. She mostly ended up falling into the task side of the LARP – that isn’t a criticism, I loved it and I wrote her that way on purpose, because I expected to be (and was) nervous and shy as a new roleplayer. But that did mean there were a lot of aspects of her I didn’t get to explore. After the LARP I wrote a fictional Wikipedia page for her, which you can read for some context. On that basis, I thought it might be worthwhile, and cathartic, to reflect a bit on her as a character. Acting is always sort of free therapy, after all, a chance to see yourself from the outside in.

Evelyn is a moral coward, sometimes a bully (mostly of herself), and a bit of a reactionary. Intellectually she should be a communist, but she can’t ever quite make it. But history has been formed of a lot worse, and when pushed, she was on the side of the angels. It was important to me writing her biography that she have a senseless, mundane and relatively young death, and a particularly European one for a life lived in relation to that continent. Drowned in Lake Constance? An overdose in a hotel in Sicily? In the end I thought it would have the most pathos for her to die accidentally on the second occasion in her life when she stood for something.

Her command style was lonely, self-serious, technical and aloof, but she did learn to trust and rely on her watch. But it’s not a simple ‘her heart grew three sizes that day’ story, because that growth happened early, then Great Bromley happened, and after that she rebuilt in a way that made her colder, more methodical, and frankly meaner. That’s when I started to think that I could see her doing this for the rest of the war. I gave her a brief period of humiliating exile to highlight how nepotistic and political Fighter Command could be, and to reinforce the idea of a constant self-doubt, but air defence is what she does, I believe she is good at it, and that gives the emotional hit that when the war ends, it just stops, and she is expected to go back to being a woman, now no longer needed or tolerated for what was then still conceptualised as men’s work. I left it unspoken in the biography, but I think she is a terror to serve under, because she has much of the same seriousness but now underwritten by even more guilt and regret. It’s the same process as one of my best/worst moments with her, finishing out her watch so she can then go and break down, but across five years rather than half an hour. The structure of Wing and a Prayer leaves you keenly aware that you are leaving the character you created at the beginning of something, rather than the end. As a matter of timescale, Evelyn will be celebrating V.E. Day in 2030, and I put a reminder in my calendar to remember her then, because amidst the real sacrifice is an opportunity to use fiction to think about what it means. The first question people have asked me when I’ve told them I’ve been on a military LARP is “Did you win?”, and what a compelling thing to be able to say, “Not yet.”

I expected to leave Evelyn at King’s Cross Station, but as I got the train north, reading H.D.‘s wartime poem The Walls Do Not Fall, looking out at the beautiful tall skies and the summer English fields, half expecting to see Hurricanes and Spitfires overhead, I realised I wanted to keep her around a little longer27. She’s an expression of (flawed) hope.

Most of all, I think it’s important that having created this whole elaborate narrative for her, the one moment that crystallises, her day of days, was the 7th of September 1940, the day when Evelyn St. Clair fought and fell and rose, per ardua ad astra. She couldn’t commit to her lover, to Spain or to communism. She fled France and Germany at the last possible moment. She hesitates, she catastrophises, she decides that everything is her fault. There is a deep well of fear and guilt in her, which experience has only deepened. But this was one day when, with the help of her comrades, she persevered. It’s just the opposite of a triumph, but in hard times may we all be granted such days.

I’m so grateful to my fellow players for having been so welcoming and such a pleasure to serve alongside, and to the organisers for everything they’ve done to make Wing and a Prayer happen, as well as for trusting me with such an important role in it on such a speculative basis. I don’t know if there’s anything else out there quite like it, but I hope so. As a wargame, as a roleplay, as a study of command, as a holiday over a weekend, I cannot recommend it highly enough. It has stayed with me for a long time, the sort of experience you find yourself imagining alternate versions2829, or different characters for whenever it’s run again. In the meantime I have been applying for other LARPs, so the bug has been well and truly caught.

In the end, I left Evelyn’s wristwatch on my bedside table and let it run down, and that was how I said goodbye to her. I’m just left marvelling at a singular experience, with wonderful people. It was a privilege from start to finish, and I can only hope that I did my part to make it enjoyable for everyone else.

- Not historically used in the Second World War, but much used in the First. Now a museum. ↩︎

- I have to commend the organisers for making the event explicitly and meaningfully trans-inclusive. So much so that I forgot I was trans for a day, which in almost ten years of transition has been a total novelty. ↩︎

- Historically, these tables were separate and geographically distant rooms connected by phone, but it’s a lot more fun and practical having it all happen in one big room. ↩︎

- And having always wanted to be one in real life. ↩︎

- ‘Ops’ if you outrank me, ‘ma’am’ if you don’t. ↩︎

- I’m only using character names here, since I’m not sure who would like to be credited and who wouldn’t. ↩︎

- Which for LARP’s sake has some pilots from every squadron, who magically join up with their compatriots in the air. Don’t worry about it. ↩︎

- That is to say, no planes ready at a critical moment. ↩︎

- Not historical. If I had tried to work a real one I would have died of plantar fasciitis around hour four. ↩︎

- As a reflection of my mindset, I’ve caught myself calling it a ‘board’ and the LARP a ‘game’ about half a dozen times writing this. ↩︎

- Something the officers liked to try and defuse with a bit of homophobia. Distinct memory of Major O. seeing me put on camouflage make-up in a very self-serious but latently transsexual way and saying something so breathtakingly offensive I still only remember the contours of it; the actual words are like TV static. ↩︎

- Another reason to stick to character names. This is all going to sound critical of the character, and I want to be absolutely clear that I think this is fantastic roleplaying, brilliantly played, and the day would have been far duller without it. As the best piece of writing advice I ever got goes, fiction is about things that go wrong. ↩︎

- But notably, not a good enough one to manage my superior. ↩︎

- If God had meant man to float, He would have given him water wings. ↩︎

- I am bitterly aware that this means that I messed up in handing over my job from myself to myself. ↩︎

- Still have the grid reference in my head today. ↩︎

- This actually required interviewing a couple of witnesses, since the way I remembered it was completely different and much more self-exonerating. An interesting thing to think about when reading historical memoirs, I suggest. ↩︎

- Yes it is. ↩︎

- Thereby deathly boring their players. Sorry! ↩︎

- They also serve, who only stand and move the teacups out of the way. ↩︎

- You may have noticed them on the board. Each squadron is assigned a five letter, two-syllable callsign for use on the radio only. Yes, this does make things confusing. ↩︎

- Sadly, this might be a wait, as the team are taking a pause from it for the foreseeable future. ↩︎

- Thus making this sentence a nested bit of foreshadowing. She had played it before, I don’t know how she kept a straight face. ↩︎

- Sorry Tangmere. ↩︎

- This is quite possibly what I had in mind when I tricked myself into not following a straight line from a raid of known direction to Great Bromley. ↩︎

- I should also at this point have had her call 12 Group and tell them to send everything with an engine and wings south or I would go up to Duxford and steal Douglas Bader’s prostheses. ↩︎

- Unexpectedly, all that time in the Essex countryside left me feeling surprisingly connected to my own Englishness, for once in a non-depressive way. ↩︎

- 70s or 80s NATO LARP when, I am asking. ↩︎

Excuse to wear a WRNS uniformBattle of the Atlantic LARP when, I am asking. ↩︎

Leave a Reply